Clay-eating, the practice known as geophagy or geophagia, has long been a puzzle to Western medical practitioners. Until recently, eating chalk, soil and other earth-related materials was an abnormal behavior, one which deprived the diet of valuable nutrients. In the southern United States, eating clay carried a stigma; those who ate clay were labeled “dirt eaters” or “clay eaters” and diagnosed with psychological disorders. Pica, the abnormal ingestion of non-food substances, remains an official diagnosis for those who eat clay, dirt, or soil, per the DSM IV and the American Dietetic Association.

Outside of the medical field, however, anthropologists and biologists are quietly revealing a more accurate explanation for the consumption of earthen clay.

Culture and history of clay consumption

In fact, eating clay is a global practice that has existed among humans since their evolution from primates, and one that continues today among traditional ethnic groups as well as numerous animal species. The practice of eating clay has been studied in present and traditional cultures from areas across continents, including present-day Arizona and California, Central and South America, Sweden and Sardinia, sub-Saharan Africa, Indonesia, and Australia.

Historically, clay eating has been associated with treatments for cholera and bacterial infection. In a practice dating back to Greek and Roman times and later absorbed by Christianity, holy clay tablets were widely distributed and traded throughout the Mediterranean region and Western Europe for use in religious customs and rituals, and as cures for poison and the plague. These clay tablets, blessed by the Roman Catholic Church, were listed in pharmacopeia as late as 1848.

A new picture of the clay eater gradually emerges as the various academic disciplines examine cultures worldwide to understand the historic benefits and the effects of eating clay. In studies appearing in academic and scientific journals over the past decade, the practice of earth eating is revealed as an evolutionary behavior that in fact developed hand in hand with the early origins of medicine.

Clay eating among pregnant women

One of the most common human populations to engage in the deliberate consuming of earth-based substances is that of pregnant women. In sub-Saharan Africa, the rates of pregnant women eating soil or clay range from 28% in Tanzania to 65% in Kenya. Clay is prepared and sold in markets, or taken from termite mounds known to be rich in minerals, and eaten at an average of 30g daily.

As scientists have sought an explanation for the historical persistence of geophagy, the body’s unique needs during pregnancy have provided the greatest clues to clay eating’s adaptive function.

Pregnancy is a period of both increased nutritional needs and increased vulnerability. In the first trimester, the fetus is particularly vulnerable to toxic insult. The pregnant mother is also vulnerable due to a compromised immune system, suppressed during pregnancies to adapt to the presence of the fetus.

Nutrition during pregnancy is increasingly demanding, especially regarding minerals such as iron and calcium, to support both the growing fetus and elevated blood production. Further, this period of nutritional need often occurs coincident with digestive difficulties such as nausea (morning sickness) and vomiting.

Another common feature of pregnancy is pronounced cravings. Connecting the dots, many scientists postulate that pregnant women craving earth-like substances actually represents a biological need associated with the demands of the body during this time. Taking clues from this intersection of bodily demands, three theories have been developed and studied to explain the therapeutic role of eating clay, both among pregnant women and on a broader cultural level:

- Clay’s nutritional mineral content.

- Medicinal use of clay to provide relief for symptoms of nausea and vomiting.

- Protection from toxins due to the actions of clay in the digestive tract.

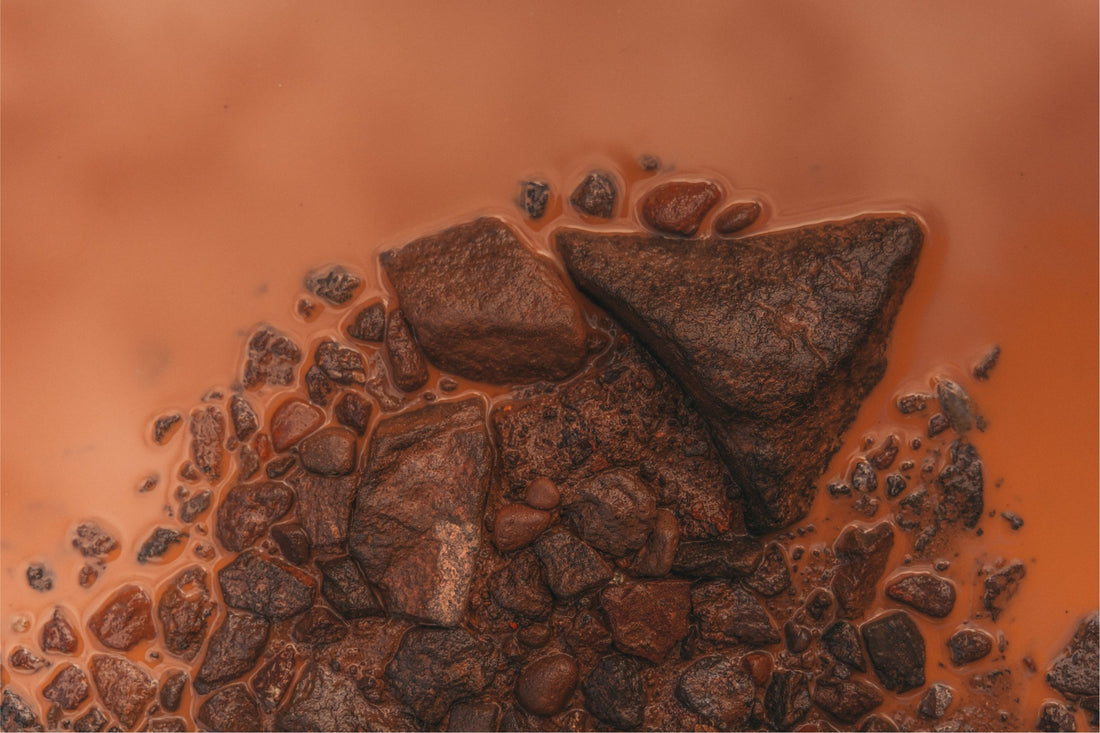

The presence of both current and pre-historic favored clay sites in Africa and other parts of the world has given scientists the opportunity to study the chemistry and mineralogy of these edible clays as they collect evidence to support these theories.

Dirt, minerals, and the nutrition hypothesis

Many of the minerals needed by the body are, essentially, dirt or rock. Though we most often consume them taken up in plant or animal form, nearly all mammalian species engage in some form of direct earth eating to prevent nutritional deficiency. An obvious example is the dietary use of salt among humans, and the frequenting of salt licks by mammals such as deer, cattle and sheep to obtain minerals such as sodium, calcium, iron, phosphorous and zinc.

Given this fact, the relationship between mineral deficiency and clay and soil eating was among the first to be examined. Scientists have hypothesized earth-eating as an adaptive behavior based on nutritional requirements, one that occurred and persisted on an evolutionary basis due to its survival benefits.

In order to test this hypothesis, Dr. John Hunter, a geologist at Michigan State University, compared the typical daily consumption of clays in Africa to the suggested dosage of several mineral supplements sold in the U.S. Testing both the mineral content and bioavailability of various clays sold for consumption in the markets of Ghana, Dr. Hunter determined that the clays compared favorably in magnesium, potassium, copper and zinc. The bioavailability of calcium in eaten clays reached 4% of U.S. Recommended Daily Allowance, with iron supplementation reaching as high as 66% of RDA.

These conclusions are especially significant as calcium intake is typically low among African populations that eat clay, and iron deficiency affects as much as 80% of the populace, made more severe by parasitic infection. According to Dr. Hunter, “These levels of mineral-nutrient supplementation point clearly to the practical value of clay eating. Normal dietary intake usually meets daily needs, and clay eating plays a supplementary role.”

A similar study simulated human digestion in the laboratory to determine the availability of nutrients in holy clay tablets regularly consumed in by pregnant mothers in Central American Belize. The study, published in The Geographical Review, found that pregnant women eating clay from these tablets could supply nearly 20% of the U.S. RDA for iron and calcium, and significant amounts of magnesium, copper and zinc.

The nutrition hypothesis continues to be studied. While some scientists believe iron-deficient anemia may cause a craving to eat earth, some believe it may be caused by eating excessive clay. Others note that, given the diversity of the cultures that historically have used dietary clays and the diverse nature of the clays themselves, it is likely that not all clays are ideal for the same set of uses or conditions, and equally likely that the ingestion of clay does not necessarily serve a single purpose.

In terms of the use of clay as a mineral supplement among pregnant women, for example, it may well be that this benefit is secondary to other benefits, such as detoxification.

Dr. Hunter also theorizes that in examples where pica may contribute to nutritional deficiencies, the problem may be the migration of geophagy to geographical areas lacking in clay sources. A clear example is the consumption of laundry starch. Though the craving and the cultural significance of eating clay was most likely transported to the U.S. from Africa, starch is a poor substitute for clay. Dr. Hunter states, “Lack of local clay in the concrete jungles of the North, pressures of poverty, and stress on kinship ties with the South lead to the consumption of laundry starch replacing traditional geophagy. But micronutrient minerals are totally lacking in the starch.”

Clay as a digestive medicinal

A more appropriate substitute for dietary clay was, however, found among African Americans in the form of kaolin, a clay mined in North Carolina and Georgia. Kaolin clays are available for purchase in shops throughout the South, marketed as “down home Georgia white dirt” and “Mississippi mud.” Those with a habit of eating kaolin clays refer to it in slang as chalk, and themselves as “chalk-eaters”, using some of the same references anthropologists have noted among African cultures, comparing its taste to the smell of fresh rain and favoring certain clays over others.

Eating chalk is not recommended, but kaolin clay may have overlooked benefits. The digestive pharmaceutical Kaopectate was formulated using kaolinite as its main ingredient, to aid in suppressing diarrhea and reducing toxic effects in the digestive system. The stigma attached to eating clay in the South may in fact be related to overuse of the substance. Similar to many pharmaceuticals, the same actions that may contribute to constipation and complications when taken in excess display therapeutic benefit when taken in times of need.

Interestingly, scientists from Louisiana State University who analyzed Nigerian clays commonly sold for consumption in West African markets discovered their composition to be strikingly like that of the clays used in medicinal Kaopectate.

In a practice perhaps precedent to industrial kaolinite mining in the U.S., villagers outside of Uzalla, Nigeria mine the clays from a depth of 30 to 90 cm from the surface, then sun-dry and smoke the blocks, transforming them into a substance known locally as eko, transporting them to market for sale throughout the region. Medicine men combine the clay with plant substances in several medicinal remedies, half of which are for problems associated with pregnancy, the rest used to ease stomach ailments and dysentery. 400 to 500 tons of this medicinal clay are produced and sold each year, a testament to their widespread use.

Given the energetic costs of diarrhea and its potentially devastating effects when coupled with dehydration and malnutrition in children, the ability of clay to act as an anti-diarrheal is notable. In the same parts of Africa where pregnant women eat clay, large percentages of children are regular clay eaters, sometimes as many as 70%. For these children, the internal use of clay may both prevent diarrhea and enable the body’s ability to digest valuable nutrients in food consumed alongside clay.

Properties of clay and detoxification

Though the study of clay consumption has revealed the potential for digestive and nutritional benefits, scientists believe the most conclusive evidence points to detoxification as a primary benefit of clay eating throughout human history. Its use appears to be one borrowed from and shared by numerous animal species, attesting to its practice not as an anomaly or aberrant behavior but instead a true adaptive practice contributing to survival and evolution.

One example from the animal kingdom is the use of clays by animal species that regularly scavenge for a wide variety of foods, often of varying toxicity. Researchers discovered that the ingestion of clays by such species, among them birds, parrots, rats and primates, enables a diverse diet without suffering the toxic effects of substances consumed. The chemical structure of earthen clays determines their suitability as a detoxicant.

Their crystalline shape includes hexagonal networks of silicon-oxygen tetrahedrons, giving them a large surface area with which to bond with potential toxins. In addition, hydroxyl ions and colloidal properties within their structure promote the ability to bind and exchange metals as well as adsorb water and other organic compounds. In cultures across continents, anthropologists and mineralogists have documented and substantiated the use of clays to reduce bioavailability of plant toxins from foods and make them more edible.

These practices are known to have been used by native cultures in present-day Bolivia, Peru and Arizona to eliminate the bitterness of wild potatoes and prevent stomach pains and vomiting, evidenced in the laboratory by the clay’s ability to adsorb glycoalkaloids found in the potato species.

Also documented is the practice of baking clay with acorn flour in breads, used historically among peoples of present-day California, Sardinia and Sweden. In examining the mineralogy of the acorn bread clays, a study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition supports the effectiveness of clays both as adsorbers of toxins and as contributors of trace minerals to the diet. Their function was found to reduce the toxicity of acorns by as much as 77%, and to potentially provide 38% of the adult RDA of Calcium.

Similarly, laboratory researchers at the University of Chicago Department of Ecology and Evolution recently demonstrated the ability of kaolin clay to adsorb three commonly ingested chemical toxins using a sophisticated technique modeling the human digestive system. Clay was found to adsorb and thus reduce the toxicity of tannic acid and quinine by 20-30%. Researchers noted that in a true human system the effect could be even greater due to clay’s ability to slow the movement of the digestive process, allowing greater absorption of nutrients and greater adsorption of toxins.

The last word on eating clay?

The study of clay eating by anthropologists, geologists, nutritionists and ecologists has in the end come full circle to teach us what we least expected to discover. Historians have long placed the origins of medicine among the Greeks, with Pasteur’s breakthroughs and the development of germ theory playing an equally important role in shaping medicine as we know it today. It seems that this vantage point is exactly what caused our cultural inability to understand the true message behind the clay eater’s practice.

Puzzling over “why people eat dirt,” we labeled earth and clay as non-food substances, but we failed to see the link between clay and our own culturally sanctioned and regularly consumed non-food – conventional pharmaceuticals. We failed to understand that the internal use of clay functions as perhaps the very first medicine practiced by humans, because it seemed outside the realm of possibility that medicine could have been intelligently practiced in pre-historic times.

But good science is particularly adept at shifting paradigms when it encounters them. Timothy Johns of the McGill University School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition has published several papers examining the evolution of early medicine. He defines medicine as the learned behavior of ingesting substances to alleviate distress or maintain health. He and other researchers have placed the earliest examples of these behaviors clearly among higher primates, such as apes and chimpanzees, who consume minerals and forage for plants to perform non-nutritive therapeutic functions.

These behaviors are learned and passed to offspring, and scientists theorize, were ultimately passed on to early man. One such example was observed and successfully analyzed by Sabrina Krief and researchers at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Chimpanzees were found to deliberately ingest a clay as well as leaves from a certain local tree. When analyzed under simulated digestion in the laboratory, it was found that the action of the clay developed clear anti-malarial properties in the leaves that were not present without the clay.

These and other examples are beginning to alter scientists understanding, not only of clay eating, but of the roots of medicine itself.

“Geophagy, the ingestion of nonfood, falls into the realm of medicine,” says Johns. “As a medicine to alleviate discomfort, clay is not different from any drug that humans in industrial and preindustrial societies take in attempting to modify their physiological state.”

Eating clay, far from an eating disorder, may instead be history’s earliest example of using the earth’s resources to solve medical problems. With recent evidence revealing clay’s common use in lowering food toxicity and promoting digestive health, this ancient practice may continue to have much to teach us about medicine and healing.

References

Dominy N.J., Davoust E., Minekus M. 2004. Adaptive function of soil consumption: an in vitro study modeling the human stomach and small intestine. Journal of Experimental Biology 207:319–324.Geissler, P.W. 2000. The significance of earth-eating: social and cultural aspects of geophagy among Luo children. Africa 70:4, 653-82.Highfield, Roger. 2008. The medicinal monkey; Roots of modern healing found in our hairy relatives. Daily Telegraph, 3 April, AL9.Hunter, John M. 1973. Geophagy in Africa and in the United States: A Culture-Nutrition Hypothesis. Geographical Review 63: 170-195.Hunter, J. M. and R. de Kleine. 1984. Geophagy in Central America. Geographical Review 74(2): 157-169.

Johns T. 1999. The Chemical Ecology of Human Ingestive Behaviors. Annual Review of Anthropology 28: 27-50.

Krief S., Huffman M.A., Sévenet T., Hladik C.-M., Grellier P., Loiseau P.M., Wrangham R.W. 2006. Bioactive properties of plant species ingested by chimpanzees in the Kibale National Park, Uganda. American Journal of Primatology 68(1):51-71.

Vermeer, Donald E., and Ray E. Ferrell Jr. 1985. Nigerian Geophagical Clay: A Traditional Antidiarrheal Pharmaceutical. Science 227:634–636.

Wiley, A.S.; Solomon, H.K. 1998. Geophagy in Pregnancy: A Test of a Hypothesis. Current Anthropology 39 (4): 532–545.

Wilson, M.J. 2003. Clay mineralogical and related characteristics of geophagic materials. Journal of Chemical Ecology 29, 1525–1547.